In our earlier blog The Tale of ‘Tail Recursion’, we have talked about tail recursion. And In this blog, we will be talking about limitation of tail recursion and its solution in scala.

Unfortunately JVM doesn’t support tail call optimization, but scala does as we have seen. However, what if we are not doing simple tail recursion like we usually do. What if on the other hand we have a function where we don’t call the function from itself but we are doing something little different.

def isEven(x: Int): Boolean =

if (x == 0) true else isOdd(x – 1)def isOdd(x: Int): Boolean =

if (x == 0) false else isEven(x – 1)

Here i have defined both function as tail recursive, instead of that it gives stack overflow exception.

But what’s the problem?

The problem manifests itself in the stack trace: even calls odd, then odd calls even, which calls odd again. Each of these invocations causes the creation of a stack frame, eating away the space that’s reserved for them.

Keeping all the stack frames would not really be necessary: when even calls odd, that is the very last thing that the even function will ever do! When odd returns, even itself returns immediately with that same value.

This jumping back and forth between isEven() and isOdd() functions is the trampoline effect.

In general, we have two tail recursive functions F(A) and G(A) and that F(A) calls G(A) but in turn G(A) also calls F(A)

Then F(A) is said to be a trampoline tail recursive function because the call stack jumps back and forth between the two functions F(A) and G(A) – hence the name trampoline.

The Scala compiler implements tail-recursion optimization for methods which call themselves in tail position, allowing the stack frame of the calling method to be used by the caller. It does this essentially by converting a provably tail-recursive call to a while-loop, under the covers. However, due to JVM restrictions there’s no way for it to implement tail-call optimization, which would allow any method call in tail position to reuse the caller’s stack frame. This means that if you have two or more methods that call each other in tail position, no optimization will be done, and stack overflow will be risked.

Because of these limitations, you need to be careful when using recursion in Scala. When writing programs, you will need to keep in mind how both the compiler and the JVM work.

Solution:

Using @tailrec annotation, it ensures that function is tail recursive, otherwise it will trigger an error if the function is not actually tail-recursive. So this will protect you from accidentally changing a function that you want to be tail-recursive function into something that’s no longer tail recursive.

To make anyone function to be tail recursive, there could be one possible solution.

@tailrec

def isEven(x: Int): Boolean = {

if (x == 0) true

else if(x == 1) false

else isEven(x – 2)

}

def isOdd(x: Int): Boolean = !isEven(x )

Since i have made ‘isEven’ function to be tail recursive, now Scala compiler will be able to optimize it.

Another solution is to use trampoline.

Think for a minute, recursion as an infinite series of functions to evaluate. And the minute you think about this infinite series of functions to evaluate what you normally do at every single stage you got a function on your hand, either you evaluate it if there’s more to do or you are done if there is result. In other words, you can quickly turn into a lazy computation to say, keep calling it until there is no more work to do. So, it becomes a lazy infinite series problem if you wanna think about that way.

Trampoline is a higher order function that takes a function as an argument and returns a new function – combinator. This new function(combinator) on invocation, will continuously call the original function passed to trampoline as long as it returns another function to execute. Once it gets back a result that is not a function, it stops executing and just returns the result of the last call.

Well thankfully, we don’t need to do much work done, it is already done for us. We just need to import: scala.util.control.TailCalls._

Scala has a utility object called TailCalls that makes it easy to implement a trampoline. The mutually recursive functions have return type TailRec[A] and return either done[result] or tailcall(fun) where fun is the next function to be called.

import scala.util.control.TailCalls.{ TailRec, done, tailcall }

def isEven(x: Int): TailRec[Boolean] =

if(x == 0) done(true)

else tailcall(isOdd(x – 1))def isOdd(x: Int): TailRec[Boolean] =

if(x == 1) done(true)

else tailcall(isEven(x – 1))

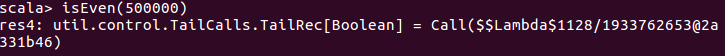

Now when i run this, notice it didn’t fail but instead, it gives a call object.What is that! it simply says i am going to be absolutely lazy so when you go and call the isEven method, isEven laid back and lazy it says i am not gonna do real work for you, i am just going to give you this call object say when i am done so this is absolutely lazy evaluation isn’t it. So how do i get the result out of it ?

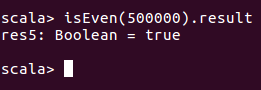

To obtain the final result from tailrec object, we use the result method.

And you can see when you call the result method, it produces the result. So you can start going very large number of values and you can see it is evaluating.

Let understand how it works:

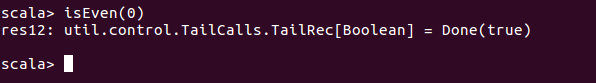

I am going to call isEven method with zero.

Notice the object you got back on hand it is a done object you got back so what is done object ?

A done object simply says i have got a result with me i have no computations to do and if you ever call me i will give you this result right that’s all it says. On the other hand, if you don’t call it with 0 but you call it with 1

Notice you got a call object and not a done. What is a call object?

A call object says i am also a TailRec object so they both are inheriting from TailRec, while the done says i am the terminal object, i have no more work to do and the call object says i am going to sit here when you call me i will invoke the function, i carry with me and simply get you back the result of that function and be done with it and the result of that function either be a done or another call and you got to go back and call one more time then if you never call it you don’t really progress any further so it is extremely lazy until you on demand keep evaluating it until you get to the very end so you can imagine what the result is going to do when you call result on it, the result is the one that simply sit there in loop through and say keep calling it repeatedly until you get a done object.

So it turns a recursion into a while loop and as a result we would never run into a stack overflow exception. So under the hood, we are just doing lazy evaluation.

So when you say “.result”, it is repeatedly evaluating the value over and over and getting the result for us eventually.

Hope that this blog is helpful for you.

References:

1 Programming in Scala By Martin Odersky, Lex Spoon, and Bill Venners

2 https://www.scala-lang.org/api/current/scala/util/control/TailCalls$.html

3 Scala for Impatient By Cay S. Horstmann

Reblogged this on Mahesh's Programming Blog and commented:

Trampoline in Scala